Chomsky Korea Union Solidarity - Kim Jin-suk

|

The Hope Bus Campaign is establishing itself as an icon of resistance to employment anxieties that are threatening worker and working-class livelihoods. The Hope Bus Campaign was launched with the goal of supporting embattled union members and Kim Jin-suk, a member of the Busan chapter of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU). Kim is currently in the 186th day of an aerial protest calling for the withdrawal of Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction (HHIC) layoff plans from the No. 85 crane at the company's Yeongdo shipyard in Busan. The buses aspire toward a "world without layoffs and temporary workers."

Kim Jin-suk, of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, on a crane at Hanjin Heavy Industries in Busan, where she has been holding a sit-in since January 6.

Amid heavy rains Saturday afternoon, a caravan of around 150 Hope Buses and 50 vans headed for the shipyard where Kim is protesting along with six union members who have tied themselves to the crane with the stated goal of protecting her. While the first round of buses had around 700 riders, some 5,000 people from all over the country got on board for this second round.

The range of participants is also more diverse. In addition to citizens unaffiliated with any group and representatives of political parties, labour activists, university students, health care professionals, religious figures, and legal professionals, the latest round saw large-scale participation by members of socially vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities, sexual minorities, eviction protesters, migrant workers, and youth.

What is the reason behind this voluntary uniting of people from different backgrounds in a show of solidarity for a labour-management conflict involving layoffs at a single regional workplace?

Not Just Someone Else's Problems

Hope Bus riders said they felt a sense of profound concern about the experiencing of HHIC union members, which "no longer seemed like someone else's problem." Poet Song Kyung-dong, who suggested the bus idea, also views this as the reason for the event's increased scale.

"With increases in temporary positions and layoffs, we are living in an insecure society," Song said.

"People do not talk about it, but there is an inherent anger about this, and this is where the solidarity has emerged from," he said.

At a time when the social safety net is inadequate, the increase in layoffs and temporary positions threatens the survival rights of the working-class. People who have experienced this situation directly or indirectly are lending their support to Kim's dedicated struggle.

"On the surface, the HHIC issue and issues involving people with disabilities do not appear to be connected with each other," said Moon Ae-rin, 31, a participant in the second round of Hope Buses who is confined to a wheelchair with cerebral palsy. "But the reality is that working conditions are poorer for people with disabilities."

"What they are going through is what I am going through," Moon said.

Police use water cannons to prevent citizens walking toward the Yeongdo shipyard of Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction (HHIC). (Photo by Ryu Woo-jong)

Dongguk University Student Council President Kwon Gi-hong, 23, who took part in the fight for a 50 per cent reduction in tuition fees, said, "We become workers when we graduate, and unless there are changes to the reality [of pressures on workers], what happened to the HHIC union members could happen to us."

The Hope Buses' impassioned call for a solution to the HHIC layoff issue appears set to develop into a larger demand for controls on corporate greed in seeking profits even at the expense of employment.

Office worker Park Jeong-hui, 27, who rode during both Hope Bus trips, noted, "In her speech, Kim Jin-suk used the expression, 'People I cannot turn my back on even if they turn their backs on me,' and I had the sense she was referring not only to HHIC union members, but to all of us who lack power and support and could be fired at any time."

"The important thing about the HHIC issue is that it is opening up a forum for questioning how society should be controlling the unjust pursuit of profits by business," Park added.

Intimately familiar with employment insecurities, workers engaged in long-term battles at Ssangyong Motor, YPR, and Valeo Compressor also began a two-day stay Saturday looking for "hope" in Busan. Thirty in-house subcontracting workers at Hyundai Motor who lost their jobs after demanding conversion from irregular dispatch worker status to regular worker status, rode into Busan from Ulsan on "Hope Bikes."

"Hyundai Motor's irregular workers are suffering oppression, with 104 of them dismissed over a 25-day period last winter sit-in protests, and around 1,000 having their bank accounts garnished as punishment," said Park Yeong-hyeon, one of the Hyundai Motor in-house subcontracting workers.

"After seeing the citizen solidarity symbolized by the Hope Buses, we are considering getting back up to fight again," Park added.

Second Round of Hope Buses

The second round of Hope Buses also drew Busan residents in their 40s and 50s back into the streets. While a number of assemblies had been held since HHIC made plans for layoffs in December, participation from citizens was slack.

"I made a promise to meet my old university friends from the 1980s at Busan Station, and I came racing here," said a 54-year-old from Changwon, South Gyeongsang, identified by the surname Park.

A 44-year-old homemaker surnamed Shin from Busan's Changseon neighborhood said, "It seemed like I could learn a lot just from watching, so I took part in the event with my two elementary school-age children."

But the riders did not have the chance to meet Kim Jin-suk. Despite struggling empty-handed to burst through the police line, they were helpless in the face of the water cannons, tear gas, and batons.

Around 3,000 participants stayed until morning occupying the eight-lane highway in front of the Bongnae intersection protesting the police suppression and mass arrests. National Assembly lawmakers from four opposition parties, including Chung Dong-young, Cho Seung-soo, and Kwon Young-ghil, met with Busan Metropolitan Police Agency Commissioner Seo Cheon-ho to demand the release of all detainees.

Seo refused the request, saying, "The release of detainees must be at the direction of prosecutors."

A key figure behind the second round of Hope Buses said, "We have resolved to organize a large-scale third round of Hope Buses within a month's time to return to Busan to protest excessive suppression tactics by police and show support for Kim Jin-suk."

Solidarity with the Bus of Hope Movement

Noam Chomsky, professor emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) needs no special introduction as the conscience and the intellect of our era. Chomsky has sent a special message to the "Bus of Hope" event currently in progress in the southeastern port city of Busan.

The police fire water cannons at citizens' peaceful protests in the early hours of July 10. Participants of the Bus of Hope Campaign were shot by tear-gas water cannon!

He expressed his support for the courageous and honorable actions and efforts for peace and justice of the Korean citizens allying with fired workers at Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction (HHIC), and hoped that there would be no "sabotage such as the use of governmental force."

Chomsky's hopes that the citizens' just efforts would not be met with sabotage, however, were betrayed by indiscriminate and hard-line suppression on the part of police.

On Saturday (July 9), the police sprayed water containing dissolved tear gas, now known to have been mixed with a carcinogenic substance, at around 10,000 "Bus of Hope" participants who were heading to HHIC's Yeongdo shipbuilding yard.

Participants, including disabled people, were arrested at random. Police did not hesitate to engage in excessive behaviour, including constantly striking down with their shields upon citizens who had fallen over after being pushed back, while those that were hit by teargas-infused water jets are said to have shown symptoms of chemical burns.

In this process, Democratic Labour Party president Lee Jung-hee and others blacked out after being hit by tear-gas water, while several tens of participants in the rally were injured.

It is impossible not to feel anger and regret at the police's outdated behaviour in using such hard-line suppression, as if carrying out a military operation, on citizens who were trying to hold a peaceful protest. The identity of those who gave the order for and those who carried out such anti-humanitarian suppression must be revealed, and they must be made to take heavy responsibility.

Despite, to use Chomsky's expression, the "sabotage" by the police, hope for Korean society could be felt among the warm, firm alliance shown by the participants in the Bus of Hope. These included prominent opposition party politicians and civic movement leaders, but the majority of them were just everyday people. They consisted of fathers who took the bus with their high school student daughters to show them what kind of place the world really was, teachers who believed their students must see for themselves the kind of irregular employment and staff curtailment that awaited them, and disabled people that regarded the HHIC situation as a universal human rights problem.

People did not regard irregular employment and staff curtailment as targets for pity and compassion, but as "my problem and our problem," and were rallying as comrades in arms of the fired workers.

Most precious of all was the fact that these people did not regard irregular employment and staff curtailment as targets for pity and compassion, but as "my problem and our problem," and were rallying as comrades in arms of the fired workers.

The authorities and HHIC must now face the fact that the staff curtailment situation has caught the attention of the world's intellectuals and foreign news agencies, and must take active steps to solve the problem.

The "Bus of Hope" has already gone far beyond the level where it will disappear from public view after just firing tear-gas water from cannons and forcibly dispersing crowds.

The more this spontaneous movement on the part of citizens is suppressed and ignored, the more powerful and wide-ranging the "Alliance of Hope" will become. •

Editorial, The Kyunghyang Daily News, July 11, 2011.

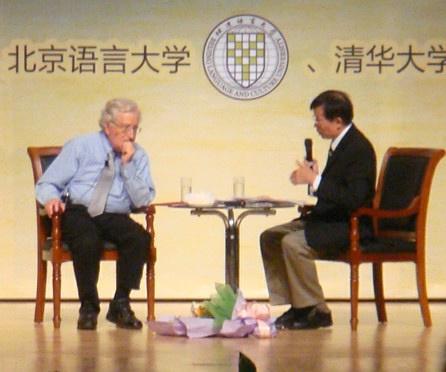

Noam Chomsky in Beijing Peking China

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Emeritus Noam Chomsky, who recently declared his support for Kim, sent an additional message of support Wednesday. The message of support from Chomsky and eleven other critical intellectuals came in response to a e-mail appear for support in resolving the HHIC situation by the National Association of Professors for Democratic Society, the Korean Professors' Union, and the Korea Progressive Academy Council.

"I would like to express my support for your courageous and honorable actions in solidarity with Korean workers, and your efforts to support peace and justice generally," Chomsky wrote in his message.

"I hope and trust that your initiatives will proceed, as they should, without attempts at disruption by the government or anyone else," he continued.

Progressive labor theorist and director of Germany's Social Economic Action Research Institute Holger Heide also expressed his heartfelt support for the battle of the HHIC workers.

Cultural researcher and Professor of Taiwan's National Tsing Hua University Chen Kuan-hsing said, "As a country famed for capturing political democracy through struggle, South Korean is rapidly losing trust by tacitly condoning HHIC's secretive layoffs."

"The South Korean government needs to make efforts to revolve the issue, and Hanjin needs to take concrete actions so that Kim Jin-suk and her colleagues can return to work," Chen added.

Central University of Finance and Economics professor and Chinese market authority Li Peng said, "I hope the resistance and fight for survival rights and justice can meet with a satisfactory resolution."

Also expressing messages of support were Simon Fraser University chair professor Michael Lebowitz, a former policy adviser to Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez; Jean-Yves Fortand, professor of France's University of Nancy; Jose Alcides Santos, a professor at Brazil's Federal University of Juiz de Fora; Arnulfo Arteaga Garcia, professor at the Metropolitan Autonomous University, Mexico; and Yun Geon-cha, professor of Japan's Kanazawa University.

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

By Lee Moon-yeong

Stumble It!

Stumble It!