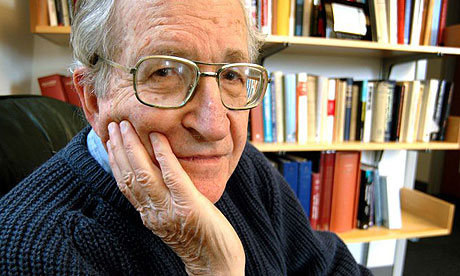

Chomsky at Columbia - Israel Zionism Facism

Noam Chomsky on Israel-Palestine Prisoner Exchange, U.S. Assassination Campaign in Yemen

MIT Professor Emeritus Noam Chomsky, the world-renowned linguist and political dissident, spoke Monday night at Barnard College in New York City about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, just hours before Israel and Hamas completed a historic prisoner exchange. "I think [Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit] should have been released a long time ago. But there's something missing from this whole story. There's no pictures of Palestinian women, and no discussion, in fact, in the story of—what about the Palestinian prisoners being released? Where do they come from?" Chomsky says. "There's a lot to say about that. So, for example, we don't know—at least I don't read it in the Times—whether the release includes the elected Palestinian officials who were kidnapped and imprisoned by Israel in 2007 when the United States, the European Union and Israel decided to dissolve the only freely elected legislature in the Arab world." Chomsky also discusses the recent U.S. assassination of U.S.-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki in Yemen. "Almost all of the critics, of whom there weren't many, criticized the action or qualified it because of the fact that Awlaki was an American citizen," Chomksy says. "That is, he was a person, unlike suspects who are intentionally murdered or collateral damage, meaning we treat them kind of like the ants we step on when we walk down the street. They're not American citizens, so they're unpeople, and therefore they can be freely murdered." [includes rush transcript]

AMY GOODMAN: Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit returned home today after five years in captivity in Gaza in exchange for 477 Palestinian prisoners. Another 550 are slated to be released in two months. Forty of the Palestinian prisoners will be deported to Syria, Qatar, Turkey and Jordan. In his first interview, Gilad Shalit expressed support for the freeing of all Palestinian prisoners. While Palestinians are holding a massive celebration in Gaza today, Palestinian prison support groups note over 4,000 Palestinians remain locked up in Israel.

We turn now to MIT Professor Noam Chomsky, the world-renowned linguist and political dissident. He spoke Monday night here in New York at Barnard College about the Israel-Palestine conflict, the prisoner exchange, and the Middle East, overall.

NOAM CHOMSKY: About a week ago, the New York Times had a headline saying "the West Celebrates a Cleric's Death." The cleric was Awlaki, killed by a drone. It wasn't just death; it was assassination—and another step forward in Obama's global assassination campaign, which actually breaks some new records in international terrorism. Well, it's not true that everyone in the West celebrated. There were some critics. Almost all of the critics, of whom there weren't many, criticized the action or qualified it because of the fact that Awlaki was an American citizen. That is, he was a person, unlike suspects who are intentionally murdered or collateral damage, meaning we treat them kind of like the ants we step on when we walk down the street. They're not American citizens, so they're unpeople, and therefore they can be freely murdered.

Some may remember, if you have good memories, that there used to be a concept in Anglo-American law called a presumption of innocence, innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. Now that's so deep in history that there's no point even bringing it up, but it did once exist. Some of the critics have brought up the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution, which says that no person — "person," notice — shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Well, of course, that was never intended to apply to persons, so it wasn't intended to apply to unpeople.

And unpeople fall into several categories. There's, first of all, the indigenous population, either in the territories already held or those that were expected to be conquered soon. It didn't apply to them. And, of course, it didn't apply to those who the Constitution declared to be three-fifths human, so therefore unpeople. That latter category was transferred into—theoretically, into the category of people by the 14th Amendment, that—essentially the same wording as the Fifth Amendment in this respect, but now a person was intended to hold of freed slaves. Now that was in theory. In practice, it barely happened. After about 10 years, the category of three-fifths human were returned to the category of unpeople by the divisive criminalization of black life, which essentially restored slavery, maybe something even worse than slavery, actually went on 'til the Second World War. And it's being reinstituted now, past 30 years of severe moral and social regression in the United States.

Well, the 14th Amendment was recognized right away to be problematic. The concept of person was both too narrow and too broad, and the courts went to work to overcome both of those flaws. The concept of person was expanded to include legal fictions, sustained—created and sustained by the state, what's called corporations, and was also narrowed over the years to exclude undocumented aliens. That goes right up to the present, to recent Supreme Court cases, which make it clear that corporations not only are persons, but they're persons with rights far beyond those of persons of flesh and blood, so kind of super persons. The mislabeled free trade agreements give them astonishing rights. And, of course, the court just added more.

But the crucial need to make sure that the category of unpeople includes those who escaped from the horrors we've created in Central America and Mexico, try to get here—those are not persons, they are unpeople. And, of course, it includes any foreigners, especially those accused of terror, which is a concept that has taken a quite an interesting conceptual change, an interesting one, since 1981, when Ronald Reagan came into office and declared the global war on terror, what's called GWOT in current fancy terminology. I won't go into that here, except with a comment, a note, on how the term is now used, without any—raising even any notice.

So take, for example, Omar Khadr. He's a 15-year-old child, a Canadian. Now, he was accused of a very severe crime, namely, trying to defend his village in Afghanistan from U.S. invaders. Obviously, that's severe crime, a serious terrorist, so he was sent first to secret prison in Bagram, then off to Guantánamo for eight years. After eight years, he pleaded guilty to some charges. We all know what that means. If you want, you could pick up a few of the details even in Wikipedia, more in other sources. So he pleaded guilty and was given eight more years' sentence. Could have—would have gotten 30 more years if he hadn't pleaded guilty. After all, it is a severe crime, defending your village from American aggressors. He's Canadian, so Canada could have him extradited. But with typical courage, they refused. They don't want to offend the master, understandably. Well, the crime of resisting aggression, it's not a new category of terrorism. There may be some of you old enough to remember the slogan "a terror against terror," which was used by the Gestapo—and which we've taken over. None of this arouses any interest, because all of these victims belong to the category of unpeople.

Well, that—coming back to our topic now, the concept of unpeople is central to tonight's topic. Israeli Jews are people. Palestinians are unpeople. And a lot follows from that as clear illustrations constantly. So, here's a clipping, if I remembered to bring it, from the New York Times. Front-page story, Wednesday, October 12th, the lead story is "Deal with Hamas Will Free Israeli Held Since 2006." That's Gilad Shalit. And right next to it is a—running right across the top of the front page is a picture of four women kind of agonized over the fate of Gilad Shalit. "Friends and supporters of the family of Staff Sgt. Gilad Shalit received word of the deal at the family's protest tent in Jerusalem." Well, that's understandable, actually. I think he should have been released a long time ago. But there's something missing from this whole story. So, like, there's no pictures of Palestinian women, and no discussion, in fact, in the story of—what about the Palestinian prisoners being released? Where do they come from?

And there's a lot to say about that. So, for example, we don't know — at least I don't read it in the Times — whether the release includes the Palestinian—the elected Palestinian officials who were kidnapped and imprisoned by Israel in 2007 when the United States, the European Union and Israel decided to dissolve the only freely elected legislature in the Arab world. That's called "democracy promotion," technically, in case you're not familiar with the term. So I don't know what happened to them. There are also other people who have been in prison exactly as long as Gilad Shalit—in fact, one day longer. The day before Gilad Shalit was captured at the border, Israeli troops entered Gaza, kidnapped two brothers, the Muamar brothers, spirited them across the border, in violation of the Geneva Conventions, of course. And they've disappeared into Israel's prison system. I haven't a clue what happened to them; I've never seen a word about it. And as far as I know, nobody cares, which makes sense. After all, unpeople. Whatever you think about capturing the soldier, a soldier from an attacking army, plainly kidnapping civilians is a far more severe crime. But that's only if they're people. This case really doesn't matter. It's not that it's unknown, so if you look back at the press the day after the Muamar brothers were captured, there's a couple lines here and there. But it's just insignificant, of course—which makes some sense, because there are lots of others in prison, thousands of them, many without charges.

There's also, in addition to this, the secret prison system, like Facility 1391, if you want to look it up on the internet, a secret prison, which means, of course, a torture chamber, in Israel, which actually was reported pretty well in Israel when it was discovered, also reported in England and in Europe, but I haven't seen a word about it here, in at least anywhere that anybody's likely to look. I've written about it, and a couple of others. All of this is—these are all unpeople, so, naturally, nobody cares. In fact, the racism is so profound that it's kind of like the air we breathe: we're unaware of it, you know, just pervades everything.

Coming to the title of this talk, it could mislead, and it could be interpreted—misinterpreted—as supporting a kind of conventional picture of the negotiations, such as they are: United States on—over here and then these two recalcitrant forces over there; the United States is an honest broker trying to bring together the two militant, difficult groups that don't seem to be able to get along with one another. Now that's—it is the standard version, but it's totally false. I mean, if they were serious negotiations, they would be organized by some neutral party, maybe Brazil, and on one side you'd have the U.S. and Israel, on the other side you'd have the world. That's literally true. But that's one of those things that's unspeakable.

AMY GOODMAN: MIT Professor Noam Chomsky speaking Monday night at Barnard College.

LectureHop: Chomsky on Israel-Palestine

He's less iconic in person.

Last night, famous linguist and leftist intellectual Noam Chomsky spoke on "America and Israel-Palestine: Peace and War" at Barnard's LeFrak Gymnasium. The line to get in was long, but Bwog's radical correspondent Peter Sterne made it inside.

A full hour before Noam Chomsky was scheduled to begin speaking, the auditorium was already beginning to fill up, and by 5:40 pm, virtually every seat was taken. Attendees continued to stream in, but they were forced to stand on the sides or sit on the floor.

Professor Chomsky began by noting the distinction between "people" and "unpeople." People, he said, were entitled to human dignity and human rights, while unpeople "look human but are considered unworthy of human rights." Historically, unpeople have included indigenous peoples and "those the Constitution considered only 3/5ths of a person." In the War on Terror, he proposes, "unpeople" now include non-Americans. He noted that even though many were critical of Obama's decision to assassinate Anwar al-Awalki, an American citizen and alleged terrorist in Yemen, they didn't mind when the United States killed non-Americans. Chomsky used this example to illustrate how Americans are considered people with certain rights that should be respected, while non-Americans are not.

The same, he argued, is true of Israelis (people) and Palestinians (unpeople) in both the U.S. and Israel. He pointed to an October 12th front-page New York Times article, "Deal With Hamas Will Free Israeli Held Since 2006" (the online version's title is different), that was illustrated with a picture of Israeli women celebrating Gilad Shalit's release. In Chomsky's view, the article focused on the impact of Shalit's release on Israelis, while largely ignoring the individual Palestinian prisoners involved in the prisoner swap, because the Palestinians are considered "unpeople."

Chomsky's criticisms were harsh, and they could easily upset Israelis, for whom Gilad Shalit's release has been a national fixation. But it didn't seem like they were designed to inflame. Chomsky didn't have the angry or self-righteous attitude of a demagogue, but rather the tired and exasperated tone of a professor struggling to explain something simple to his students. It was obvious that he was extremely knowledgeable about the subject of Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Arab relations, and he proceeded to detail a brief history of diplomacy between Israel, Egypt, the U.S., Palestine, and other Arab states. He made a strong case that the United States has generally acted not to advance peace, but to advance its own interests, and that these are often tied to Israel's. Serious and fair peace negotiations, he argued, would have to be mediated by a neutral third party—not the U.S.—and be based on the internationally-recognized 1967 borders.

One example of the U.S. and Israel choosing their own interests above peace, according to Chomsky, occurred in 1971, when President Anwar Sadat of Egypt offered the Israelis full diplomatic relations in exchange for the return of the Sinai Peninsula (which Israel had occupied since the 1967 war). Israel rejected the agreement, preferring to move settlers into the Sinai, and the United States, under Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, supported the Israeli rejection. According to Chomsky, this was partly for racist reasons: a memo circulated in the State Department arguing that Egypt posed no threat to Israel because "Arabs don't know which end of the gun to hold!" With both Israel and the U.S. refusing to negotiate, Egypt launched an attack to reclaim the Sinai in 1973, which resulted in a war that killed 20,000 people and nearly caused nuclear war between the Americans and Russians. After the war, Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin met at Camp David to negotiate the 1979 Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty, which was almost identical to Sadat's original proposal eight years earlier. Though these negotiations are often seen as a diplomatic triumph, Chomsky argued that the Camp David negotiations and 1979 treaty should instead be considered a diplomatic failure. After all, he explained, if the U.S. and Israel had simply accepted Sadat's offer in 1971, they could have avoided a disastrous war.

The audience seemed supportive of Chomsky during his lecture. He received a standing ovation at the end of his talk, and the crowd spontaneously broke into applause and laughter at particularly interesting moments in his lecture. The line "[Palestinian prisoners] are all unpeople, so nobody cares. The racism is so profound that it's like the air we breathe" was particularly well-received. The explanation that "the United States and Israel punished Palestinians with sanctions for voting the wrong way [i.e. for Hamas] in free elections. That's called 'promoting democracy,'" also caused a great deal of laughter.

The way questioners addressed Chomsky soon revealed that the audience were not uniformly fans. Two clear trends were discernible from the lines of questioning, which contributed to the divided atmosphere. Those who addressed their questions to "Dr. Chomsky" or "Professor Chomsky" asked why the United States tolerates Israel's behavior and what Israel should do about illegal settlements to achieve a two-state solution, while those addressing "Mr. Chomsky" asked about Ehud Barak's proposal to Arafat during the 2000 Camp David Accords (a central point in Dershowitz's celebrated "In Defense of Israel") and Binyamin Netanyahu's proposal for ostensible "negotiations without preconditions" at the U.N. a few weeks ago. In sum, around half the participants in the Q&A asked challenging questions, just as Alan Dershowitz had called for.

columbiaspectator

By Katie Bentivoglio

Spectator Senior Staff Writer .. Published October 19, 2011

Painting the world in stark dichotomies, famed linguist Noam Chomsky explained the Israel-Palestine conflict in simple terms to a crowded audience in LeFrak Gym: "Israeli Jews are people and Palestinians are 'unpeople.'"

Sponsored by the Center for Palestine Studies at Columbia University, Chomsky's speech "America and Israel-Palestine: War and Peace" was a harsh critique of American foreign policy in Israel. Professor of Linguistics Emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Chomsky is one of the foremost American intellectuals to speak against American foreign policy concerning Israel and Palestine.

In a speech that read like a laundry list of Israeli-Palestinian history, he returned to the people/unpeople theme many times to explain Israel's treatment of Palestinians and America's acquiescence.

"Remember, these are all 'unpeople,'" he said. "So naturally, no one cares."

In addition to his psychological analysis, Chomsky focused on what he considers to be the greatest obstacle to moving forward in the peace process: the United States. The United States is one of Israel's last allies, offering political and financial support to the country despite decades of criticism from the international community.

"Israel offers a lot to the United States," Chomsky said, referring to American investments in Israel—especially in military capital and military technology—and its role as a strategic American ally in the Middle East. He also referred to "cultural" similarities, saying that both the United States and Israel share a history of removing indigenous peoples from their lands. "We did it, so it's got to be right. Jews are doing it, so it's got to be right," he said.

In the end, Chomsky said there are two simple options: that things continue the way they are or Israel and the United States allow for a two-state solution.

"If you're opposed to a two-state settlement at this point, you're telling the Palestinians to get lost," he said. "Of all the problems in the world, this has to be the easiest to solve," he said.

Following his speech, questions ranged from aggressive attacks on his political positions to practical inquiries about the details of his proposal for peace.

One student challenged Chomsky's claim that Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak walked away from a peace settlement during the 2000 Camp David Accords, saying it was Palestinian Authority Chairman Yasser Arafat who refused Barak's offer to give Palestinians all of Gaza and most of the West Bank. But Chomsky said that the terms of the agreement were unworkable from the beginning. "Clinton recognized that no Palestinian, no Arab, would ever accept the terms that they proposed," he said. "There's no need to discuss it."

He also questioned the veracity of many students' facts. "There is an official story, which is true, but like most official stories, it falls apart quickly if you look at the facts," he added.

Despite enthusiastic applause through much of his talk, Chomsky's wording attracted a crowd of mixed opinions.

"When he says 'unpeople,' what he means the audience to understand is racism," said Ryan Arant, SIPA. "But what I think he's describing are traditional power dynamics between the powerful and the powerless."

"There are real things to talk about," Arant added. "But calling Israel and the West racist is not one of them."

But others considered the event a valuable learning experience.

"It was a good way to get a view of it from a well-informed source," said Yaas Bigdeli, SEAS '14. "I was impressed," she said, adding that she was drawn to Chomsky by his fame and a desire to learn about the Israel-Palestine conflict.

But as Bigdeli noted, the notably dry Chomsky did end on a positive note.

"I think it's kind of optimistic," he said. "Because it means that the future is in our hands."

Internationally-recognized author, linguist, and activist Noam Chomsky will be speaking at Occupy Boston in Dewey Square tomorrow, October 19 at 6:15 pm as part of the Howard Zinn Memorial Lecture Series. Chomsky has already released statements of support for both Occupy Boston and Occupy Wall Street, and we are honored to be hosting him.

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home