tony blair cartoons - The Chilcot inquiry

The Iraq Inquiry, also referred to as the Chilcot Inquiry,[1][2] was announced on 15 June 2009 by the British Prime Minister Gordon Brown. He initially announced that it would look into the country's role in the Iraq War and would be held in private [3][4]. The early plan to hold the inquiry in secret attracted wide criticism and was subsequently reversed.[5] Brown stated, "no British documents and no British witness will be beyond the scope of the inquiry."[3]

The Iraq Inquiry is currently an ongoing inquiry by a committee of Privy Counsellors with broad terms of reference to consider the UK’s involvement in Iraq from mid-2001 to July 2009. It will cover the run-up to the conflict, the subsequent military action and its aftermath with the purpose to establish the way decisions were made, to determine what happened and to identify lessons to ensure that in a similar situation in future, the UK government is equipped to respond in the most effective manner in the best interests of the country.[6]

The timing and nature of the inquiry generated a certain amount of political controversy. Conservative Party leader David Cameron dismissed the inquiry as "an establishment stitch-up", and the Liberal Democrats threatened a boycott.[7]

The open sessions of the inquiry commenced on 24 November 2009, televised from the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre.

It is expected to report its findings after the 2010 General Election, due before Thursday, 3 June 2010.

don't forget that MANY terror incidents were CIA/Mi6/Mossad false flag attacks. Always ask who benefits? Big money for weapons.

don't forget that MANY terror incidents were CIA/Mi6/Mossad false flag attacks. Always ask who benefits? Big money for weapons.The committee of inquiry, the members of which were chosen by Gordon Brown, includes:

* Sir John Chilcot (chairman), a career diplomat and senior civil servant who was previously a member of the Butler Review.

* Sir Lawrence Freedman, a military historian, and Professor of War Studies at King's College, University of London. His memo outlining five tests for liberal military intervention was used by Tony Blair in drafting his Chicago foreign policy speech.

* Sir Martin Gilbert, a historian who supported the invasion of Iraq and claimed in 2004 that George W. Bush and Tony Blair may one day "join the ranks of Roosevelt and Churchill."

* Sir Roderic Lyne, former Ambassador to Russia and to the United Nations in Geneva, previously served as private secretary to Prime Minister John Major.

* Baroness Usha Prashar, a crossbencher, member of the Joint Committee on Human Rights, and the current chairwoman of the Judicial Appointments Commission.

Bush illegal wars 911 inside job investigation

War stories of 2009:

First up: The drone war over Pakistan. This time last year, it was most definitely underway. But in 2009, it kicked into high gear. The Obama administration launched more than 50 reported robotic strikes, killing several hundred people. Compare that to 2008, when there were just 36 drone attacks.

The character of the drone war changed, too. A year ago, the Pakistani government was denying any connection with the attacks. So was the U.S. military. And the idea that Blackwater was somehow mixed up in the whole thing was a plot twist worthy of Hollywood. But that was before Google Earth spotted U.S. Predators parked on a Pakistani runway; before the Air Force let slip that their drones were running missions east of the Durand Line; and before the CIA publicly announced that it was cutting Blackwater’s contract for rearming the drones. By May, the unmanned attacks had become such an open secret that CIA director Leon Panetta confessed that the robotic campaign was “the only game in town in terms of confronting or trying to disrupt the al Qaeda leadership.” (This, despite the militants’ apparent understanding of how the drones were targeted, and how to see through the robotic planes’ eyes.) That view was shared by some in the White House, who wanted to recast the Afghanistan fight along the lines of the drone-heavy effort in Pakistan. But counterinsurgency experts continue to worry that the robotic attacks could destabilize the region as they continue into 2010 and expand to a new front: Yemen.

The Inquiry – membership, scope and expertise

What are the Inquiry’s remit/terms of reference?

As Sir John Chilcot said at the launch of the Inquiry on 30 July 2009, the purpose of the Inquiry is to examine the United Kingdom's involvement in Iraq, including the way decisions were made and actions taken, to establish as accurately and reliably as possible what happened, and to identify lessons that can be learned. The Inquiry is considering the period from 2001 up to the end of July 2009.

Who are the members of the Chilcot Inquiry Committee?

Sir John Chilcot (Chairman), Sir Lawrence Freedman, Sir Martin Gilbert, Sir Roderic Lyne, and Baroness Usha Prashar.

Who picked the members?

The Prime Minister appointed the members of the Committee. Opposition parties were consulted.

Why don’t you have politicians on the Inquiry team?

The Committee’s membership is a matter for the Government. Sir John has, however, discussed his approach to the Inquiry with the Government, leaders of Opposition parties, Chairmen of relevant House of Commons Committees and other interested Parliamentarians. The Committee will continue to discuss the Inquiry with politicians as the Inquiry progresses.

What experts does the Inquiry have to assist it, and what experience do they have?

The Iraq Inquiry Committee has appointed two advisers to help it conduct its work. General Sir Roger Wheeler, the former Chief of the General Staff, will assist the committee on military matters, and Dame Rosalyn Higgins, the former President of the International Court of Justice, will advise on international law.

How qualified are the Committee members to ask searching questions in a forum such as the hearings?

All Committee members are Privy Counsellors with long and distinguished careers, whether as historians, senior officials or as the Chairman of a number of highly respected boards and commissions. They are highly experienced at asking questions to uncover and establish the truth. They will draw on this experience in their approach to the hearings and the Inquiry more generally.

Why is the Inquiry being held now?

Governments decide the timings of inquiries. The Government had repeatedly said that an Inquiry should be held once combat troops had left Iraq so as not to undermine their role there. Combat troops have now withdrawn and the Government judged it was the right time to begin an Inquiry.

Will the Inquiry look into issues that are being considered by other proceedings?

There may be issues that are subject to other ongoing proceedings – for example, legal proceedings or police investigations - on which it would not be appropriate for this Inquiry to comment. We will decide that on a case-by-case basis, subject to legal advice.

How is the Government co-operating with the Inquiry?

As the Prime Minister told the House of Commons, “no British document and no British witness will be beyond the scope of the Inquiry.” The Government has assured the Inquiry of the full co-operation of the relevant Departments.

Top

The hearings, witnesses and evidence

When will the Inquiry start taking evidence?

The initial public hearings for the Iraq Inquiry are due to run from Tuesday 24th November 2009 until 17th December, break for Christmas, then start again during the week of 4th January 2010. It is expected they will run until early February. It is expected that further public hearings will be held in June and July 2010.

Will records of proceedings be available on the Inquiry website?

The Inquiry team intends to put records of the public evidence sessions on the website.

Will all the documentary evidence be published on the website?

The Committee intends to publish the key evidence with its report at the end of the Inquiry. It may also publish material on the website as the Inquiry progresses where this will help increase public understanding of its work.

Can members of the public and media attend hearings?

Yes, there will be seats both for the media and the public for the public evidence sessions.

What are the procedures around public attendance?

Members of the public will be asked to follow certain standards of behaviour, similar to those in a courtroom, although this is not a judicial inquiry. A leaflet will be given to anyone entering the hearing room outlining these standards.

Will the Inquiry proceedings be televised?

The Committee wants to ensure that as many people as possible have access to what is happening in the public hearings, either direct or through the media. That includes the public hearings being televised and streamed on the internet. It will be for the television companies to decide what they will broadcast.

Whom will the Inquiry call to give evidence?

Having considered the issues and material which it has requested or has been drawn to its attenttion, the Committee will invite those it judges are best placed to supply the evidence it needs to conduct its task thoroughly.

Will names of witnesses be provided in advance?

The Inquiry will publish on its website a timetable for public hearing sessions on a rolling basis.

Why are you releasing protocols covering the running of the hearings?

The Inquiry wishes to be as open and transparent as possible about the approach and processes it will adopt. The Protocols seek to establish a framework of mutual trust between the Inquiry and the witnesses in order to achieve the core aims of the Inquiry to establish a full and reliable account of what happened from which it will identify lessons for the future. The Inquiry expects that there will be interest in how it conducts its business, and in particular how it ensures fairness to witnesses whilst ensuring that it is able to elicit a full, accurate and truthful account of what happened.

Why would someone need to give evidence in private?

The Protocols set out that the Inquiry will hear all evidence in public unless the Committee judges it should be heard in private. The factors the Committee will take into account in considering whether evidence should be given in private include whether the evidence they will give would, if revealed in public, damage national security or other vital national interests. The Committee will also consider the official role of the witness, including their seniority, and any other genuine reasons such as health or security that would make it difficult for them to appear or to be entirely frank in public.

Will you tell witnesses the line of questioning they will face?

In order for the evidence sessions to be as effective as possible, and in order to ensure fairness to the witnesses, the Inquiry will provide guidance on the matters that the Inquiry wishes to cover in the hearing, and any documents the Inquiry wishes to refer to. The witnesses will not be told of the precise lines of questioning they will face.

What protection do witnesses have to speak freely?

The hearings are not covered by Parliamentary or other privilege. The Committee expects all witnesses to provide truthful, fair and accurate evidence. The Inquiry welcomes the fact that the Government and Services have extended an immunity from disciplinary action to serving officials and military personnel who give evidence or otherwise assist the Inquiry, as this will help reassure witnesses that they can provide frank and honest evidence.

Should a witness feel unable to answer questions due to a genuine fear of self-incrimination of a criminal offence, it would be open to the Inquiry Committee to consider whether, in order to secure the greatest possible openness and co-operation, it would be appropriate to seek an undertaking from the Law Officers that evidence provided to the inquiry will not be used in criminal proceedings against them, in accordance with the usual practice in inquiries.

What will the Inquiry do if it receives evidence or information about criminal offences?

If the Inquiry receives credible evidence that criminal offences have been committed that has not previously been referred to the investigating authorities, it would be obliged to refer that evidence to the appropriate investigating authority.

If a witness isn’t able to consult with a lawyer isn’t there a danger that they might incriminate themselves or libel someone?

All of the witnesses have been offered legal assistance in preparing for the hearings and are entitled to have a legal representative present to advise them during the hearing. However, the legal representative will not be permitted to ask questions or make representations during the hearing.

Will evidence given in private be explained in public, and, if so, when and how?

If evidence cannot be given in public for one of the reasons set out in the Protocols, the Inquiry will give careful consideration to how best to draw on and explain in public what was covered in the private session including, where appropriate, redaction or anonymisation. This may take place during the hearings or in the final report.

How can I submit information to the Inquiry?

You can submit your information to the Inquiry electronically using the form in the “Contact” section of the website. Alternatively, if you prefer, you can write to us at:

Iraq Inquiry, 35 Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3BQ.

Does the Inquiry have a Freedom of Information policy?

The Inquiry, itself, is not a public authority for the purposes of the Freedom of Information Act, so the Act does not apply. However, in addition to its hearings being open to the public and the media wherever possible, the Inquiry's website will contain transcripts of public hearings and other key information relating to the work of the Inquiry.

The outcome

Will the Inquiry say whether anybody involved in the Iraq conflict should face criminal charges? Will it be able to apportion blame?

The Inquiry is not a court of law. The members of the Committee are not judges, and nobody is on trial. But if the Committee finds that mistakes were made, that there were issues which could have been dealt with better, it will say so.

What difference will the Inquiry make?

The Inquiry will provide a reliable account of events that will help identify lessons to guide future foreign policy decision-making and decisions regarding conflict and post-conflict situations.

When and how will the report be published?

The Committee intends to complete its task as quickly as possible but cannot at this stage know how long the Inquiry will take. Sir John Chilcot said at the launch of the Inquiry that the earliest the Inquiry would report was likely to be late 2010, and possibly later. The Prime Minister in his statement of 15 June said that he wanted the Committee to publish its report as fully as possible, disclosing all but the most sensitive information essential to our national security. It will be published as a Parliamentary paper and debated in both Houses of Parliament.

Will there be an interim report?

If, as the Committee works through the evidence, it considers that it would be helpful to publish an interim report, it will do so. But it is more likely, given the purpose of the Inquiry – identifying lessons for the way government acts and takes decisions in the future - that its report will be a single one at the end of the Committee’s deliberations.

How much will the Inquiry cost/how much is the budget?

The Government has assured the Committee that it will have the resources it needs to do its job properly. At the same time, it is determined to ensure that it runs the Inquiry efficiently and does not waste public money. The Inquiry will publish its costs.

New Statesman, June 19, 2006

You might think the Massachusetts Institute of Technology would be well designed, but you would be wrong. I arrived to see the legendary Professor Noam Chomsky with five minutes to spare, but it then took 20 minutes of misdirections and meanderings before I finally reached MIT's Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, where Chomsky has reigned supreme for 51 years.

I arrived hot and sweaty, because I had been told by some that he did not suffer fools gladly, though others had insisted he was unfailingly courteous. People tend to have widely divergent, passionate views of Chomsky: to many he is a revered beacon of academe and politics, while critics exult in dismissing him as (take your pick) a fraud, a Zionist, an anti-Semite (he is Jewish), an off-the-chart commie, an agent of the CIA, Mossad, the KGB, MI6 and so on. The world is so split between Chomskyites and anti-Chomskyites that there is even a book called The Anti-Chomsky Reader.

My anxieties, though, turned out to be groundless. I was greeted by a softly spoken man in a speckled green pullover who could have been a decade younger than his 77 years, and who showed immediate empathy. "It's a crazy building," he said. "Can you imagine the point of having a faculty office with angled walls where you can't even put a bookcase or blackboard?"

Hardly a minute has passed in the last half-century, it seems, when Chomsky has not been pouring out ideas and passions. He has published more than 100 books, ranging from his seminal 1957 work on linguistics, Syntactic Structures, to this year's Failed States: the abuse of power and the assault on democracy, which deftly turns the Bush administration's description of countries such as Afghanistan on the US itself. Linguistics is hardly my field, but I had tried in advance to get a feel for just how important his academic work is. I knew that his basic theory, put exceedingly simply, is that language is not something merely picked up by children in the course of growing up, but that we all come into the world with a linguistic framework embedded in our brains. My further research faltered, though, when the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy told me his work had evolved so that the "grammaticality" of a sentence could be explained by the theorem: X-NP1-V-NP2-Y->(1)X-NP2-be+enV-by+NP1-Yx. Then a friend who has a doctorate in linguistics came to my rescue: "Chomsky redid linguistics the way Freud redid psychology," she explained in an e-mail. That was enough for me to place the man's academic standing in context.

And so, that settled, to politics. We spoke about Iraq and Afghanistan, about Blair's Britain ("I guess if the country's going to blindly follow US orders it's going to inherit the threats that come with that"), about how Messrs Bush, Blair, Straw and others were war criminals and why America is a failed state. But we began with the story dominating the media that day: the killing of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in Iraq. Chomsky was not joining in the triumphalism.

"He was certainly a leading gangster and I don't think there's many people outside of his village in Jordan that mourn him. He's had a horrible role that was basically created by the Iraq invasion, which we can't escape responsibility for. He had a loose connection with al-Qaeda, mostly symbolic, with each trying to exploit the other. But that whole system which we call al-Qaeda is not an organisation, it's a network of networks, a lot of loosely interconnected people. What the effects [of killing al-Zarqawi] will be in the massive terrorist apparatus that's been created by the Bush-Blair invasion, one can only guess. The invasion was an enormous stimulant for terrorism, as was anticipated."

Mastery of detail

Chomsky's unremitting clarity and his seeming mastery of detail somehow defy interruption or argument, but they are wondrous to behold. When we talk about Bush, Blair and co being hauled before the War Crimes Tribunal, I mention Milosevic and he switches subjects without pausing. The case against the Bush administration is stronger, he insists, than that against the late Serb president. "Remember, the Milosevic Tribunal began with Kosovo, right in the middle of the US-British bombing in late '99 . . . Now if you take a look at that indictment, with a single exception, every charge was for crimes after the bombing.

"There's a reason for that. The bombing was undertaken with the anticipation explicit [that] it was going to lead to large-scale atrocities in response. As it did. Now there were terrible atrocities, but they were after the bombings. In fact, if you look at the British parliamentary inquiry, they actually reached the astonishing conclusion that, until January 1999, most of the crimes committed in Kosovo were attributed to the KLA guerrillas.

"So later they added charges [against Milosevic] about the Balkans, but it wasn't going to be an easy case to make. The worst crime was Srebrenica but, unfortunately for the International Tribunal, there was an intensive investigation by the Dutch government, which was primarily responsible - their troops were there - and what they concluded was that not only did Milosevic not order it, but he had no knowledge of it. And he was horrified when he heard about it. So it was going to be pretty hard to make that charge stick."

And Saddam Hussein? "Saddam Hussein is, of course, a leading monster, but he is being charged right now with crimes he committed in 1982 - with having killed about 150 Shiites after an assassination attempt in 1982. Well, 1982 is a pretty important year in US-Iraqi relations. That's the year in which Ronald Reagan removed Iraq from the list of states supporting terrorism, so that the US would be able to provide their friend Saddam with large-scale aid. Donald Rumsfeld had to [go to] Iraq to tie up the agreement. That included the means to develop weapons of mass destruction, chemical weapons, and so on.

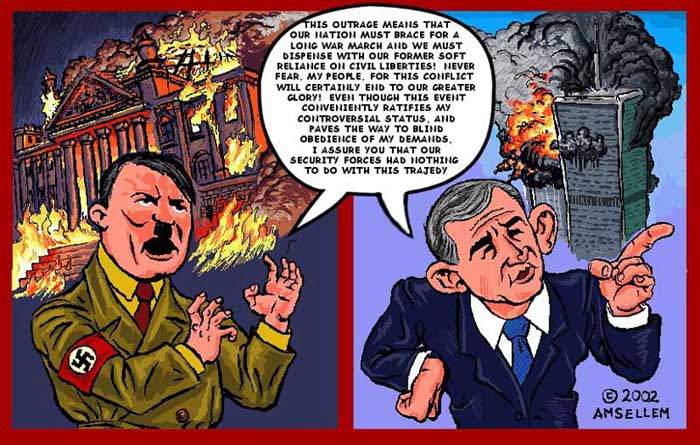

Reichstag 911

"A large point of that was to punish Iran. The weapons that were provided by the United States and Britain and Germany and Russia and France and plenty of others were supporting Iraq's aggression. The US and Britain and those others were supporting it, so why aren't they in the dock next to Saddam Hussein?"

I mentioned the hanging by Iraq of my then colleague on the Observer, Farzad Bazoft - and my feelings when a deputation of US senators went to Baghdad soon afterwards to see Saddam, and one of them told him that his regime's main problem with the west was media perception. Chomsky did not miss a beat. "That was April 1990, a few months before the invasion of Kuwait. It was a high-level senatorial commission led by Robert Dole, who was the next presidential candidate for the Republicans, to convey President Bush's greetings and to assure him that the United States had their best wishes for him and that he should not pay attention to the carping in the media because we have this free-press thing here . . . They were grovelling, and that was a couple of months before the invasion [of Kuwait]."

It's worse in Britain, he says. "Jack Straw, in 2002, was wailing about Saddam Hussein's atrocities - and right before that he turned down an application for asylum from an Iraqi dissident who had escaped the torture chambers. And he turned it down with a letter saying that [the man] could be sure that if he went back to Iraq he would be treated properly by their justice system." He likes the description of Blair's Britain, he tells me, as pillion rider on the American motorcycle.

And Afghanistan? "I think Afghanistan, if we look at it, is one of the most grotesque acts of modern history. There's a lot of reinvented fables about it. But the war was undertaken explicitly on 7 October [2001] with Bush's announcement that unless the Taliban handed over to the United States people who the US suspected - not knew, but suspected - were involved in 9/11, then the US would bomb the people of Afghanistan.

"Admiral Boyce, I think it was, the British commander, then announced a change in the war aims after about three weeks of bombing. He said that the bombing of Afghanistan would continue - I wish I could remember the exact words, but it was something like 'until the people of Afghanistan overthrow their government'. They bombed Afghanistan with the knowledge that there were about five million people, according to their estimates, who were at serious risk of starvation."

So he believes that the attacks on Afghanistan were worse than those on Iraq? "Every crime is distinct. I mean, is it worse than invading South Vietnam in 1962? Is it worse than the Russian invasion of Afghanistan?"

Understand the crimes

Which brings us back to war-crimes trials. Did he seriously envisage Bush and Blair in handcuffs at The Hague? No: charging them would be symbolic. "What was important about the Nuremberg trials was not that they hung however many people it was, but that the German population were given the proper means to understand what the crimes were. I want their crimes to be fully understood, to be in elementary school textbooks, and ensure that those of our countries which tolerated these crimes should look themselves in the eye."

Then we move on to Iran, and Chomsky's methodical deconstruction of US and British policies there. In American eyes, he says, there's only one event in US-Iranian history in the past half-century. "That's 1979, when Iranians committed a crime: they threw out a tyrant installed by a US-British military coup, and they took hostages. And they had to be punished.

"Well, did anything else happen in the last half-century or so? Yes. The US and Britain overthrew the parliamentary government, installed a brutal tyrant, supported him right through the years of torture and violence. As soon as he was overthrown they turned to supporting Saddam Hussein's invasion of Iran, which killed hundreds of thousands of Iranians - many with chemical weapons provided by the US and others. Right after that they imposed sanctions which have crushed the population.

"That means that for over 50 years the US and Britain have been torturing the people of Iran." Yet they remain defiant, Chomsky says, and for that they have to be punished. "Starting in the summer of 2003, two interesting things happened. First, all of a sudden, the reason for invading Iraq was not weapons of mass destruction. It was to bring democracy to Iraq and the Middle East and the world . . . But the other thing that happened which has been little noticed is that there was already the beginning of building up a government media campaign about Iranian nuclear weapons.

"And as Bush's popularity declined, the intensity of this campaign increased. Maybe it's just coincidence, but I don't think so. In fact, the Iranian alleged nuclear weapons are now providing a pretext which will be used for a permanent US presence in Iraq. They're building the biggest embassy in the world in Baghdad which towers over everything, they're building military bases. Is that because they intend to get out and leave Iraq to itself? No. If you're staying in Iraq you have to have a reason. Well, the reason will be that you have to defend the world against Iran."

Admiration and hatred

By now Chomsky's assistant is knocking on the door and leaving it ajar, a signal that time is nearly up with the man the New York Times has called "arguably the most important intellectual alive today". The leading monitor of academic journals says he is the most cited authority in the world today: yet that blend of admiration and hatred, of reverence and revulsion, runs as powerfully as ever through the US bloodstream when his name comes up.

Stanford's Professor Paul Robinson wrote in the New York Review of Books that Chomsky has a "maddeningly simple-minded view of the world", while Marxist-turned-neo-con pundit David Horowitz, co-editor of The Anti-Chomsky Reader, describes him as the "ayatollah of anti-Americanism". Chomsky even figured on the list of targets of Theodore Kaczynski, the so-called Unabomber, and he is frequently given police protection, even on the MIT campus, though he insists he does not seek it.

He says, however, that when he takes his grandson to a baseball game he enjoys being part of mainstream America: "It's my country," he told me, with what I thought was just a hint of defensiveness. His latest book, though, defines his country as a failure. There are three main criteria for failed states, he says: unwillingness or inability to protect its citizens from violence, insistence that they are not answerable to international law or to any external consensus, and failure to implement true democracy.

The Bush administration, he believes, "has got no interest, or very little interest" in protecting American citizens from terrorism - containers coming into US ports, for example, are not inspected properly - "but the most serious threats are literal threats to survival, the threats of nuclear war and of environmental destruction". And Bush is not protecting Americans against those either.

Showing scant respect for international law or external consensus, too, has a pedigree in the US going back over almost two centuries of expansionism. "There's a lot of outrage about the Bush Doctrine, but what about the Clinton Doctrine? It said that the United States has the right to undertake unilateral use of force to protect key markets, resources and investments."

The third crucial sign of America's failure, he says, is that "there's a huge gap between public opinion and public policy. Both political parties are well to the right of the population on a host of major issues, and the elections that are run are carefully designed so that issues do not arise."

But Americans still voted overwhelmingly for either Bush or Kerry in 2004, didn't they? "I don't know if you watched the presidential debates. I didn't but my wife [they have been married since 1949] did. She has a college PhD and taught for 25 years at Harvard and is presumably capable of following arguments. She literally couldn't tell where the candidates stood on issues, and people didn't because the elections are designed that way." By whom? "The public relations industry, because they sell candidates the same way they sell toothpaste or lifestyle drugs." Who are their masters? "Their masters are concentrations of private capital which invest in control of the state. That funds the elections, that designs the framework."

That was all very well. But if we could wave a magic wand what would be the first thing President Chomsky would do? "I would set up a War Crimes Tribunal for my own crimes, because if I take on that position [I would need] to deal with the institutional structure and the culture, the intellectual culture. The culture has to be cured."

The clearly much-practised assistant has knocked three times now, but Chomsky moves on to the "Fissban" treaty, "which would place the production of fissile materials under some kind of international control, so that then anybody could get access to them for nuclear power but nobody could use them for nuclear weapons. Unless that treaty is passed, the species will almost certainly destroy itself."

The US, he explains, is willing to have a treaty "as long as it's not verifiable". The matter came to a vote in a UN committee in November 2004 and the result was 147-1 in favour, with two abstentions, he says. "The one was, of course, the United States. The abstentions were Israel, which reflects that they have to vote for the US - and the other was Britain. So it's more important [for the Blair government] to be a spear-carrier than to save the species from destruction."

Pillion passenger

And so we had come full circle, back to Britain the pillion passenger. By the time the assistant knocked a fourth time, I was starting to leave. In the corridor outside I spotted a board crammed with squiggles and formulae every bit as impenetrable as that encyclopaedic explanation of Chomsky's work. It was precisely because he can plumb such academic depths, I mused as I wended my way back across the Charles river to Boston, that nobody should blithely dismiss Chomsky's political views as those of a crackpot.

In fact, a thought came to me that will probably not only seem heretical to many Chomskyites but will also outrage the White House enough to get me sent to Guantanamo: what struck me was that even though Chomsky was brought up in a thoroughly Jewish household, went to Hebrew schools and camps and had what he calls a "visceral fear" of Catholics in childhood, there was something profoundly Christian about the thrust of his message to me that morning.

He loathed violence and aggression, that was clear; yet he sought vengeance only in a symbolic sense. Though passionate, he did not seem bitter. Maybe I saw him on a good day. But if there's one virtue of the US to which Chomsky repeatedly returns it is its unique tolerance for free speech. And what better example of that could there be than to listen to a Hebrew-speaking, self-proclaimed libertarian socialist preaching the virtues of Christian pacifism in Bush's America of 2006?

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home